Interoperability requires a technical framework of hardware, software and, of course, information. Each has issues surrounding it, but the latter is an area that the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT (ONC) is seeking consensus on in order to create a standardized data set that all electronic health records will contain.

The U.S. Core Data for Interoperability (USCDI) initiative from the ONC aims to develop a minimum set of data classes that will be required to be interoperable on a national scale and implemented by the end of 2018. The data classes are meant to be iterative and to expand strategically over time. Additional classes are being identified for implementation in 2019 and 2020.

In other words, the USCDI’s goal is to establish what information all electronic health record systems should be able to share, no matter where you are in the United States, and no matter what differences exist between the systems and service providers of any given healthcare facility. The USCDI has a built in Task Force, the goal of which is to make recommendations about drafts of the policy and its proposed expansion process, as well as ways to incorporate stakeholder feedback.

Purpose

It may seem obvious, but the truth is that not all health systems or providers are on the same page about what information needs to be provided by health records, nor are they on the same page about what should be shared.

Health insurance companies, care providers, hospitals and patients all need access to the same information in order for the continuum of care to run smoothly. The current draft of the USCDI is being reviewed by various organizations around the country. Many support it, as it does a lot of good things for interoperability efforts. The National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics (NCVHS) noted the following outcomes as positives to come from USCDI:

- Sets semantic standards for data exchange, ensuring data is accurately captured, accessed, exchanged and used

- Limits data sets to a predetermined core, making it realistic for stakeholders to accomplish exchange

- Able to expand core data sets over time

Data Classes

A data class, as defined by ONC, is “an object that carries data about particular health information and is usually created to address a specific use case or a series of related use cases. It is made up of specific data items. Examples of data classes include prescription records, lab results, the OASIS and MDS data sets, PHQ-9, the list of social determinants of health, and a problem list. Coding systems such as ICD-9, ICD-10 and SNOMED are not data classes.”

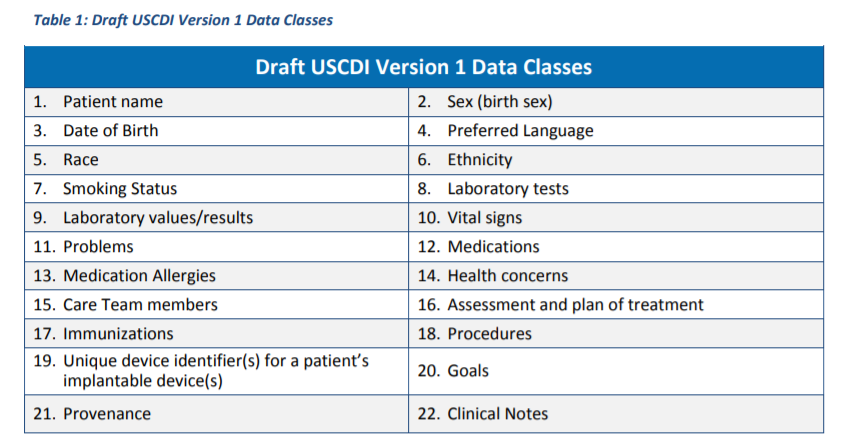

The following table from ONC’s USCDI Draft outlines the first data sets to be required under the policy.

Following these are expansion data classes which are broken down into two categories based on how the USCDI Task Force ranks them in terms of being a priority. The first category is a “candidate” class, or data classes considered to be next in line for inclusion in the USCDI. To be in this category, a data class has to have a clear definition and proven applicability across a number of use cases. The data has to also have been technically standardized under either FHIR or Consolidated-Clinical Document Architecture (C-CDA) specifications.

The next class in terms of priority is considered “emerging.” These are considered critical to nationwide interoperability, but the need for them to be moved up to candidate status is unclear.

Growth

As the USCDI data sets grow, each iteration comes under review from industry stakeholders. Many are already providing comments on the current candidate class, set to be rolled out in 2019.

For example, the NCVHS pointed out in its feedback that areas included in the candidate class such as cognitive status, family health history and functional status are not highly standardized. Another field, reason for hospital admission, typically presents a number of problems in terms of providing reliable data.

Furthermore, there has been some criticism of items that seem likely to be a source of redundancy, such as Diagnostic Imaging Reports and Special Instructions.

The former is not much different than clinical notes, being a document that contains a specialist’s interpretation of image data. It conveys an interpretation being provided to a referring physician and already becomes part of the patient’s medical record.

The latter is part of the emerging data classes, but is noticeably similar to the Discharge Instructions data class currently mentioned in the candidate data classes.

For the complete list of USCDI data classes, take a look at the USCDI Draft from ONC.

Importance

Beyond identifying what data needs to be made available as part of nationwide interoperability efforts, the USCDI’s goal is intrinsically linked with the definition of information blocking. According to a blog post from health IT solutions company and EHR vendor Cerner, “if the USCDI is a floor as to what electronic health data should be available for exchange, then failing to provide that data in the required format upon request through the Trusted Exchange Framework may be considered information blocking.”

The 21st Century Cures Act applies the terms information blocking and interoperability equally to apply to health care providers across the spectrum of care. That means all providers, in all venues, must meet USCDI requirements. Additionally, the use of Certified EHR Technology (CEHRT) is required by programs such as meaningful use and the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). CEHRT systems will benefit from this standardized data to facilitate the level of interoperability needed across the industry.

In the end, the USCDI represents a common set of requirements for all providers using health IT products, vendors of that technology, and Health Information Networks. What remains to be seen is how well prepared the aforementioned parties are to comply with its rollout and what kind of technological hurdles many will face during implementation.